Food security not possible without changing our attitudes

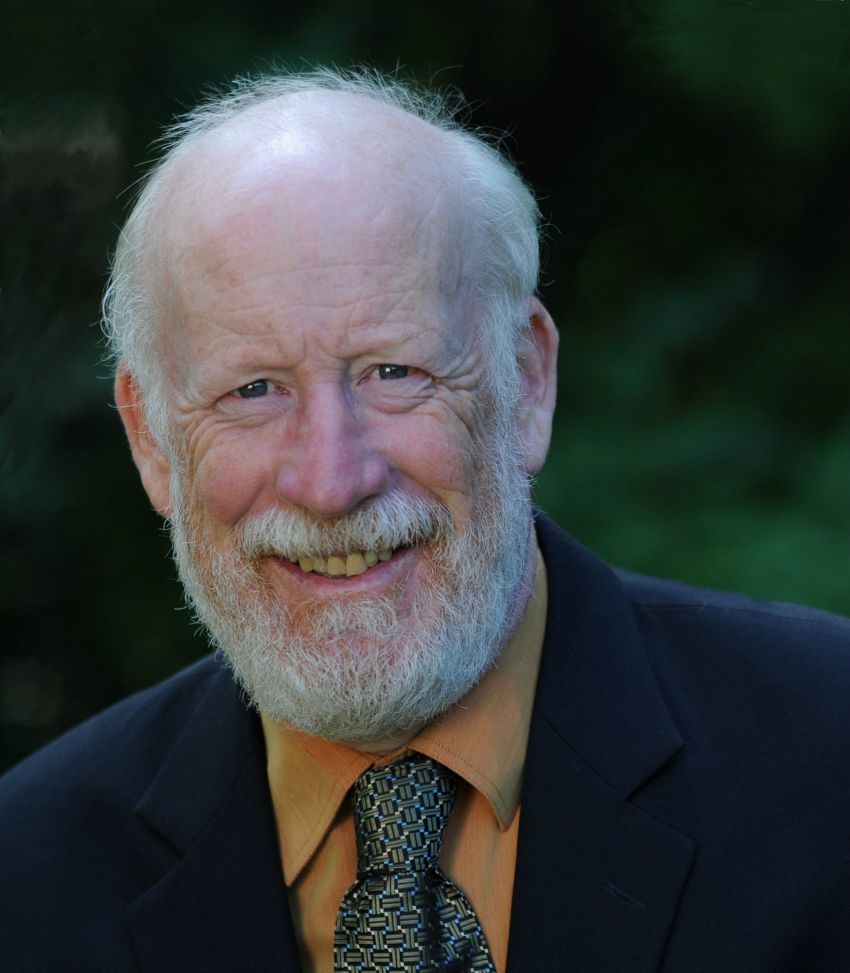

George Penfold, regional innovation chair at Selkirk College, doesn’t believe that we have a food security problem. What he does believe is that Canadians have an appetite problem instead. An appetite for inexpensive, convenient foods year round that is also reliant on using a great deal of agricultural land for one purpose – grain. If people are worried about the future of food, Penfold suggests that they start looking at how they eat.

“It’s been interesting from my perspective having been directly or indirectly involved with agriculture all my life to see the current resurgence of the whole question of food under the label of food security,” said Penfold. “But when you get into conversations about what does that actually mean, there are all kinds of different perspectives folks have about what food security means to them personally. Some of it has to do with a genuine fear about lack of food. I personally don’t buy that. Haiti has a food security problem. Somalia has a food security problem. For the most part our problem in North America is that we have too much food, or at least we consume too much food, and the wrong kind of food.”

Penfold started his position with Selkirk three years ago with the purpose of providing information and research in support of community development issues in the West Kootenay / Boundary. Food has been a big part of conversations he’s been having as his work carries him around the region. Penfold comes from a farming background so he has some insight into the farm production experience. At College over Coffee, hosted by Selkirk College at Jogas Espresso on Mar. 25, Penfold engaged in a discussion about food.

While Penfold agrees that while some people in our communities have food security problems, the average citizen doesn’t have worries about food security. He stressed that there are probably different motivations and different ways to describe the current focus on eating locally grown foods.

Some reasons are social and health perspectives of having enough to eat; environmental perspectives such as using less energy for food production and eating organically; the desire for good quality food; and the influence of lifestyle perspectives – the 100 mile diet trend. Penfold suggested that the focus really should not be food security but a drive to support regional agriculture and food self reliance.

“There has been a lot of movement toward the idea of reducing our vulnerability as consumers moving to organic food, food with less oil, pesticide chemical input and that’s also behind a longer term concern about oil – where is it going to be in price at some time down the road and what’s the consequence of that going to be in our whole production system,” said Penfold.

“A big component of agriculture strategies is how do we create jobs and improve the wealth in our community. The question is: is there a way to make our agriculture and food supply more efficient so that it can be less vulnerable to outside forces – it’s about increasing the resiliency of our food system.”

But reality takes another chunk out of the idea of self-sufficiency when it comes to food from Penfold’s view. In B.C. reports estimate that the average person consumes about 80 kilograms (KG) of grain directly and another 395 kg of feed grain consumed indirectly as meat, eggs, milk, cheese, etc. For the West Kootenay / Boundary area, with 90,000 people, self-sufficiency comes at the price of about 42,750 tonnes of grain or 17,100 hectares of grain production.

With about 53,000 hectares currently being farmed in the region (2006 Canada Census), the current 18,000 hectares of field crops would almost all have to be transferred over to grain to be truly self-sufficient in the current food lifestyle. Forget vegetables, range lands, and horse feed, the farms would all be in grain. Or we could choose to deforest many more hectares of land to meet our current food habits.

“We cannot achieve food security on our current patterns of consumption. It would be very expensive – we’d have to have greenhouses to have the food we enjoy year-round. Our consumption patterns are part of what we need to think about if we’re really serious about food security because we have a climate and a set of land and water resources that can feed us, but not in the style that we’ve become accustomed to,” said Penfold.

In addition to a certain lack of available land for grain production to feed our cows, and make bread, Penfold was also very clear that, despite everything, if the actual value of agriculture doesn’t increase, there will continue to be an exodus of farmers.

In 1961, Penfold explained, Canadians spent 19% of their total household expenses on food (not including alcohol) and that decreased to 9.3% by 2005. What that means is that the average person is not willing to pay a lot for their food. The ability for a farmer to make a living from his work is critical to the availability of local food, as critical as land, water, climate, commodity marketing and processing, storage facilities, and access for customers.

We need to change our appetites, said Penfold, in order to even consider food self-sufficiency. People cannot expect to have cheap, convenient, non-resilient foods if the sources are more localized.

“As consumers it would be nice to get local food. There isn’t much of a chance of it if that’s all we’re willing to pay for it. The reality is the food that we get coming from other countries is: a) produced at industrial scale, b) produced in a climate that can generate three – five crops a year rather than one or two, c) based on very low labour rates. We can’t compete with that. But that has become part of our lifestyle,” explained Penfold.

“So as long as we expect to go to the grocery store and buy a head of romaine lettuce on a cold blustery day in February for $1.89, we’re not going to get close to self-sufficiency. This is the single most significant barrier to self-sufficiency. We are simply not willing to pay enough to farmers to grow food and generate a reasonable enough income for them and their families.”

Improved food self-sufficiency comes through the commitment of consumers, businesses and producers to regional production, processing and purchasing. But even with improved local systems, Penfold is not convinced that everything can be done in local areas.

“We’re not there yet. In the interim – grow your own, eat low energy, buy from local producers, buy ethically and stock your shelves,” advised Penfold. “Do not be reliant on Safeway for your personal food security. There’s a lot more possibilities that you can take personal responsibility for in terms of regional food self-sufficiency, that you can act on now that are possible if we can get a system in place where someone else is taking care of all that.

“In thinking about self-sufficiency, I think we need to start looking at broadening our options a little bit. I’m not sure that trying to create a wall around the Boundary, around the West Kootenay, or even around the entire region is going to get us where we want to go.”

Comments