Medical Journals Spotlight Kootenay Lake Hospital: Standards in emergency medical care needed

By Suzy Hamilton, The Nelson Daily

Nelson fell from fourth to last place in its failure to rescue critically ill patients in a 2011 report by the Fraser Institute.

And the doctor citing the Fraser Institute’s Hospital Report Card (www.hospitalreportcards.ca), which used data from 2009, says Nelson residents are still at risk 11 years after the cuts to Kootenay Lake Hospital services were made by Interior Health in 2002.

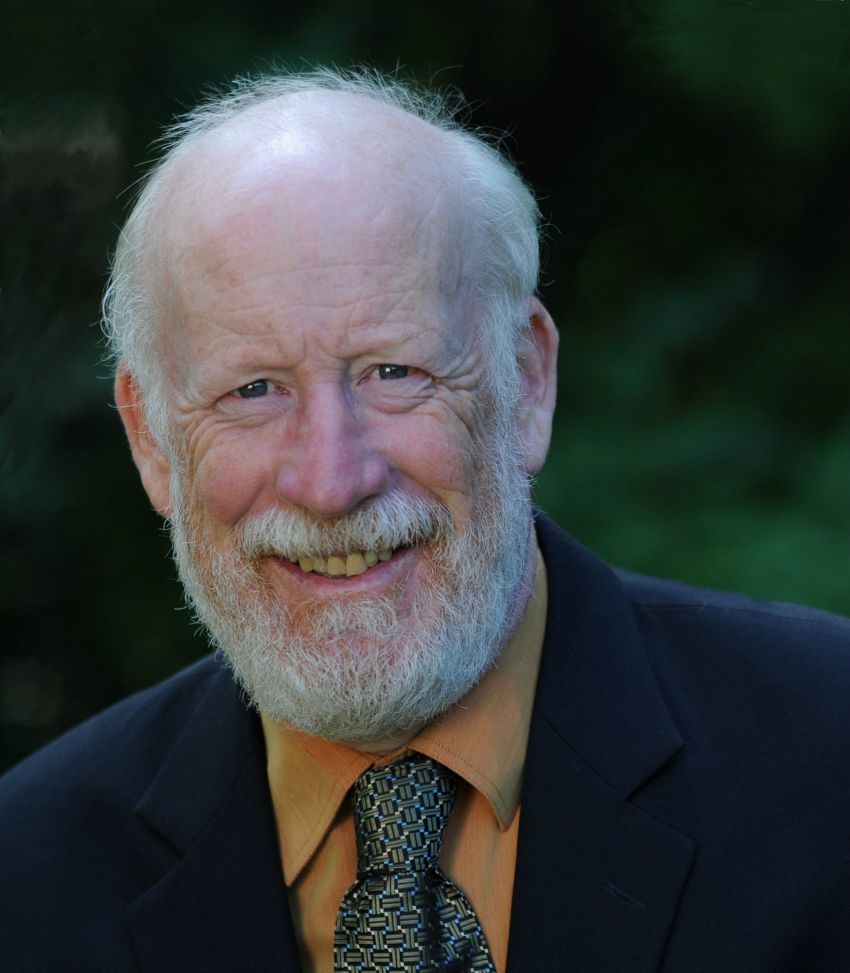

Dr. Richard Fleet, lead author of two papers published this week in medical journals has said: “Without a continuously operational CT scanner, general surgeon, ICU and efficient critical care transport system, citizens of Nelson and the surrounding area continue to be at risk.”

Currently Chair of Research of Emergency Medicine at Laval University’s medical school,

Dr. Fleet was emergency room doctor and chair of the department at KLH from 2006-2010. His experience in Nelson working under dire conditions has inspired a national research program on rural emergency care.

“Everything we’ve done has been inspired by Nelson,” he said from his office at Laval.

That may be a negative example most Nelsonites don’t wish to continue.

When Fleet arrived in Nelson, services had been centralized in Trail, 74 km away. The intensive care unit, general surgicalservice, and inpatient mental health ward were closed andlaboratory and radiography services reduced.

As a result, he said, over 1,500 patients per year requiredtransfer for workups, consultations, or a higher level ofcare,frequently on an emergency basis.

“Much of what I saw there freaked me out,” he said. “The ski hill, the roads, the outdoor recreation…there was a disproportionate amount of trauma and the reliance on medivac was very concerning. How many do you need to medivac all over the province at the same time? Relying only on this is logistically impossible.”

Fleet and fellow doctors began advocating for the return of services to KLH, a subject he discusses in the article Patient advocacy by rural emergency physicians after major service cuts: the case of Nelson BC, which appears in the April, 2013 edition of the Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine (CJRM) www.cma.ca/cjrm

The doctors and community members were successful in gaining permission for Nelson to fund raise for a CT scanner for KLH, a three-year endeavor that was successfully completed and installed in 2011. The scanner, however is only operative during business hours, Monday through Friday, and not on weekends. Patients must travel to Trail outside those hours.

However they did not regain a general surgeon, ICU beds or an independent review, which they believed necessary for proper emergency treatment. Furthermore, Fleet pointed out in the CJRM article, “the response by the health authority instilled fear in fellow physicians. Several physicians were concerned about possible consequences such as additional service cuts and recruitment issues and about being further ostracized.”

The doctors were also worried about “coverage gaps” which in essence means no appropriate doctor is available, such as the gaps in medical coverage that have been seen at the Kootenay Boundary Regional Hospital.

“Over a one year period following the media events, five full time ED physicians and one internal medicine specialist resigned,” quoting Fleet in the CJRM article.

A big part of the problem, Fleet said, is that there are no standards for rural emergency careand no one is monitoring. The issue has hardly been researched he said. A complicating factor for rural Canadians, some 20 percent of Canadians, is that we are in poorer health and are at greater risk for trauma.

And, the Canadian Health Act, which stipulates equal access to medical care for all Canadians has a “where and as available” clause that provides a gray area for interpretation for health authorities.

Thus, a positive outcome to Fleet’s work experience in Nelson has been his research, community studies and advocacy into nationwide standards with an eye, to changing the federal Health Act.

In Nelson’s sister city Baie-Saint-Paul, Quebec, for example, the situation is very different. It is a city similar to Nelson, artistic, with a ski hill, and on the water. That community was undergoing similar threats to service cuts when, according to Fleet, the Quebec government “stuck it’s neck out”.

“They found out about Nelson, and by using Nelson’s situation we prevented service cuts. The question was, ‘How many doctors will leave if we don’t do this?’”

Now, Fleet uses Nelson in papers and at conferences to show the importance of doctor advocacy and the impact of service cuts.

“Nelson is extremely famous,” he said.

In an editorial authored by Fleet in the March, 2013 online Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, entitled Access to emergency care in rural Canada: should webe concerned?, he further uses Nelson as an example of what is lacking in emergency care. (http://www.cjem-online.ca)

Quoting from the text: “As a priority, research should focuson defining rural standards for emergency care, developand test relevant indicators, identify causes for disparitiesin access to care, and, finally, measure outcomes. Inspiredby the work in the field of rural obstetrics, data from suchstudies could lead to the development of models thatwould guide service attribution decisions to rural areas inthe context of our complex geodemographic realities.”

Fleet admits emergency health care is complex. Without standards, monitoring and legislation the problems can only get worse.

He does have one solution for Nelson, however. Return the services to KLH as a pilot study. “Let’s do at least a pilot project. Let’s reinstate surgical, a 24/7 CT scanner and improve transportation and test it out for five to seven years.”

He acknowledges that the effects of his research may take years to bring about changes. “When I speak at conferences, some of the criticism is that it is virtually impossible to provide standards. But the answer to that argument is, maybe we should do a little better than that.”

Fleet made a pledge to a Kootenay patient hours before she died.

Fleet opened the CJRM article with this: “At the end of my shift she said, ‘Doctor, if I don’t see you again, promise me one thing: please continue the fight.’

“Her transfer did not go well, the plane was delayed several times and she eventually was transferred by road ambulance — a five hour transport,” he wrote. “She died before surgery. We wish to dedicate this article to the memory of this patient.”

Comments