The Crisis of Extreme Capitalism

Our current incarnation of capitalism — variously referred to as savage capitalism, extreme capitalism or euphemistically as the “free market” (free of any constraints) — is in one of its periodic crises. For years many assumed that the smart people who ran the system and benefitted from it would find a practical way to fix it. The problem is that the solutions are all framed within an ideology that makes that extremely unlikely. That ideology, neo-liberalism, is like a religion. Once you are a true believer you see other solutions as heresy.

Milton Friedman, the Chicago School economist whose extreme economic theories helped transform the English speaking world, was not fond of democracy. While most academics would shy away from suggesting that democracy was a problem, not Friedman. At a conference on Freedom, Democracy and Economic Welfare in 1986, he challenged an audience member who had placed democracy at the pinnacle of human achievement — not so, said Friedman. “You can’t say that majority voting is a basic right…. That’s a proposition I object to very strenuously.” He later wrote: “One of the things that troubles me very much is that I believe a relatively free economy is a necessary condition for a democratic society. But I also believe … that a democratic society, once established, destroys a free economy.”

The transnational corporations and finance capital that now rule the world owe their dominance in no small measure to the global application of Friedman’s ideas. In the service free economy — which really means unfettered capitalism and the pathological greed that underpins it — Friedman’s followers have made sure that democracy’s threat has been quashed.

But the “free economy” romanticized by Friedman and his ilk is anything but. Completely dominated by giant corporations whose wealth outstrips all but the richest nations, economic freedom does not exist for anyone else, including the vast majority of businesses who are at the mercy of financial institutions and mega-corporations. This says nothing of workers whose “freedom” to sell their labour now means they are free to compete with those who earn a few dollars a day thousands of miles away from their communities.

A free economy has always been a euphemism for liberated capital, and globalization is its obvious expression. While the behaviour of genuine markets as envisioned by Adam Smith were actually rooted in the customs, mores and culture of communities, this is less and less often the case. Market behaviour is now typically that of Goldman Sachs or hedge funds. Their coldly calculated and amoral decisions affect every community on the planet and everyone living in them.

But this 30-year history of liberating capital has had exactly the effect that many predicted: a persistent consumption crisis. Capitalists cannot sell all the goods and services they are capable of producing. The crisis has been delayed a number of times — most notably by the globalization of production.

But the 2008 meltdown stripped away all the camouflage from a system that could not prevail. In Canada as well as in other developed Western nations, the crisis has been delayed by cheap goods from China and other low-wage countries, and by the liberal use of credit. But nothing in nature or economies stays the same for long and these two factors can no longer save extreme capitalism from its crisis.

The latest report to demonstrate just how dire the situation is was actually ordered up by Jim Flaherty himself in apparent response to Justin Trudeau’s focus on the middle class in his leadership campaign. The report revealed that after-tax income for the middle 20 per cent of Canadians (the classic middle class) had increased by just seven percent between 1976 and 2010 — or .2 per cent a year. (1976 just happens to be the year that the campaign to liberate capital began in earnest.) This just reaffirms the 2008 figures from the Centre for the Study of Living Standards which showed just how out of balance the power of capital had become over labour. The increase in annual median earnings (adjusted for inflation) for a full-time, full-year employee between 1980 and 2005 was a mere $53 — in other words a real increase of about $2 a year.

As stunning as that figure is, even more revealing is that labour productivity over that period increased 37 per cent. One very concrete way of comparing the power of labour and capital is to examine the share of the proceeds of increased productivity each receives. This time capital took it all — virtually every dime over a 25 year period. Had incomes grown at the same rate as productivity, the median income would have been $56,826 in 2005 instead of $41,401. But they didn’t. Capital took it all because it could, because year by year democracy and its constraints on the “market” were steadily eroded.

In that missing $15,000 a year you can find the crisis of consumption Canadian chapter. If millions of Canadian workers and families had actually kept pace with productivity, the astonishing level of debt they now face would be much lower and they would be spending money in the economy. Last October the debt to income ratio of Canadian families hit a new record of 163.4 per cent. The comparable figure in the U.S. — where it is also considered dangerously high — is 110 per cent. As if that wasn’t bad enough, money borrowed against home equity totals $206 billion, equal to 12 per cent of Canadian GDP (it’s four per cent in the U.S.).

The impression left by many economic writers is that Canada is primarily an export economy, but the fact is that some 70 per cent of the economy is domestic. If people aren’t spending and the global economy is struggling, capitalism has a problem. Capital, in its drive for complete liberation from community and society, has outsmarted itself. In Canada the largest corporations are now sitting on some $700 billion in cash that they can’t invest in productive activity because demand has flatlined.

To solve the consumption crisis, governments and the corporations they serve need to put money back in the hands of people who will spend it. But the iconic One Per Cent can only spend so much. It is they who have scooped up most of the increased wealth in the past 30 years, creating a level of income inequality not seen since 1928. Yet, to shift income to middle and working class families would entail once again constraining capital, something no political party, not even the NDP, even hints at.

The one remaining method of increasing disposable income is, of course, cutting taxes which governments have done with reckless, ideological abandon for the past twenty years. Yet even here some 60 per cent of the total wealth “liberated” at both federal and provincial levels has gone to the wealthiest 10-15 per cent and to large corporations. For the latter these tax cuts have simply added to their mountain of unusable cash.

Tax cuts actually threaten to exacerbate the crisis, not solve it. While few CEOs dare admit it, government spending actually is the best way for corporations to externalize many of their costs: health care, education, social stability and perhaps most obviously, physical infrastructure. A CCPA study released last January concluded that Canada would have to spend $30 billion a year for the next decade to bring infrastructure spending back to historic levels. Ottawa accounted for 34 per cent of such spending in 1955 in the days when our current infrastructure was being built. But by 2003 it was down to 13 per cent.

It would be instructive for someone to calculate how much of the $700 billion of unspent corporate cash came from corporate tax cuts — and then apply it to the social and physical deficit.

This refusal of the federal government to collect adequate revenue to address this huge deficit in infrastructure is one of the best examples of just how perverse neo-liberal ideology has become. A modern economy cannot function efficiently with crumbling infrastructure — roads, bridges, mass transit systems, sewer and water systems — yet government policy continues to contribute to the crisis. And this is just one category of service that corporations rely on. Cuts to education, medicare and the lack of investment in social housing and child care are equally irrational from a business perspective.

Yet the current management committee of capitalism will respond to its crisis based on the theory that got them here in the first place — Milton Friedman’s edict that democracy is the problem. The greater the crisis, the more democracy will have to constrained. If the medicine doesn’t work, increase the dose. Inequality will not be addressed, it will be institutionalized.

And here you have the rationale for the gradual development of the security/surveillance state. Is the United States ahead of Canada on this front? We can’t know for sure. The massive invasion of privacy and violation of civil liberties in the U.S. exposed by whistle-blower Edward Snowden has been justified as the necessary price Americans have to pay to keep them safe from terrorism. It is more likely the price Americans — and perhaps Canadians — will be forced to pay as extreme capitalism anticipates future domestic resistance to its behaviour.

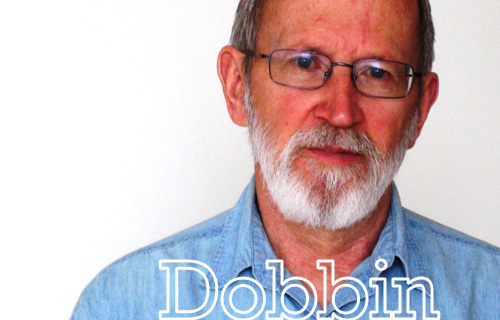

Murray Dobbin is a journalist, author, and activist. This column originally appeared on his blog. Reprinted with permission.

Comments