Op/Ed: We need to talk more about death

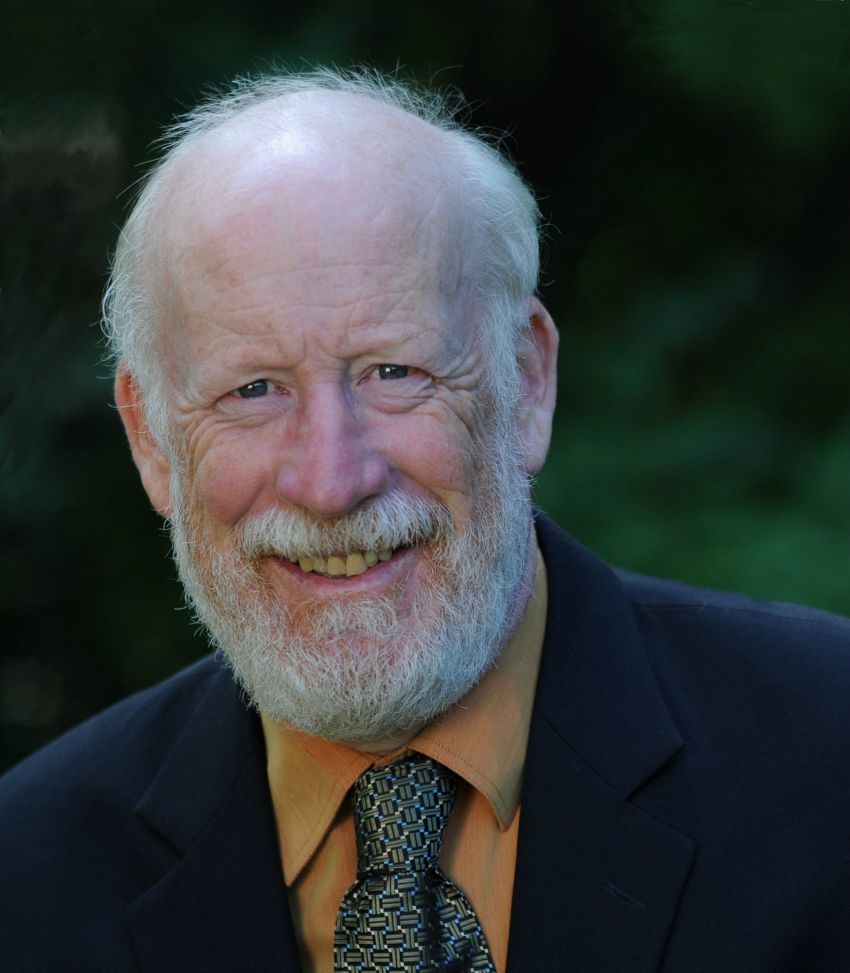

By Susan Srigley, Professor, Nipissing University. This article first appeared in The Conversation.

As a death doula and professor who teaches about dying, I see a need for more conversations about death.

A growing number of folks may have heard of the death-positive movement, death cafés or death-friendly communities — each of which are animated by the understanding that welcoming our own mortality could improve the quality of our lives.

There is truth to these claims. Both as a person who has taught courses on death, dying, and spirituality for more than 20 years, and as a death doula, thinking about dying and working closely with the dying has fostered in me a deep appreciation for what it means to live well and meaningfully.

However, my university students have often told a different story. Both informally in class discussions, and also in a public presentation about why death education matters, for the online Lifting The Lid International Festival of Death and Dying, many have expressed how their learning with me signals their first times talking about death.

When I hear this, I am aware of how our society needs to do a better job at nurturing more conversations about death, and building communities that support people navigating questions surrounding death and dying.

Denying death

The easiest way to exile death from our conversations is to label it “morbid,” ensuring we never need speak of it.

My first lecture in every death class begins with a discussion of the pervasiveness of death denial in dominant modern western culture.

I ask my students: “How do people react when you tell them you’re taking a course on death?” Invariably they have heard things like:

“That’s so morbid!”

“How depressing/dark/strange/weird!”

“Why would you want to study that!?”

My courses are designed to introduce students to the study of death through history, culture, religion and spirituality, ritual, literature, ethics and social justice

We explore social and cultural barriers affecting how services are structured and the implications for end-of-life care. For example, racism and inequities in health care and other institutions contributes to dangerous disparities in treatment and life outcomes, influencing Black, Indigenous and racialized communities’ collective trauma surrounding dying and death.

Students read and learn about how humans have understood and interpreted death, as well as some of the pressing social issues that we face in contemporary death care and practices.

Inspired by the work of Dr. Naheed Dosani, palliative care physician and health justice activist, I now include a class on palliative care for people experiencing homelessness and dying in the streets.

Anishinaabe death doula Chrystal Toop, a Member of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation, also visits my class to speak about compounded trauma of death and collective grief experienced by Indigenous Peoples, and why she created her own Indigenous death doula training to reclaim cultural teachings.

I also bring what I have learned as an end-of-life companion from hours sitting with and listening to people who are facing their own death or the death of those they love.

The gentle skills learned there are discernment, attention and compassion. As students reflect on what they will take with them from the course, they perceive the value in this kind of experience I bring to the classroom as much as in an article on palliative care and its history.

Negative consequences of denying death

My courses on dying and death have always drawn students from other humanities programs like English, fine arts and history. But over the years, more students from the professional programs, such as nursing, criminal justice and social work are enrolling.

While students’ professional programs — for example, in nursing or social work — seek to address various topics surrounding aging, trauma, death or end-of-life care in varying ways, students also need opportunities to think about their own mortality and, to cultivate some self-awareness in order to be present for others experiencing death and dying.

Some of my nursing students raise questions like: How do they talk to the loved ones of patients who are dying? What should they say?

These questions are hard enough when death is expected. They are exceptionally difficult when it isn’t, when the death is of a young person, a child or a baby.

New level of awareness

Students also express their disappointment and confusion because what they face in the aftermath of death and loss is often isolation and solitude.

While research about how to support children and young people navigating death amplifies the need for open and sensitive discussion, some students, especially white, middle-class students, speak of experiences of having been shielded from death by those who thought shielding them was the best way to protect them from fear and anxiety.

Simply providing the safe space to begin to have these conversations goes a very long way towards assuaging their fear and grief.

In part this is because supporting the passage of life to death, and supporting grief, is (or should be) a collective experience.

Community death care is everyone’s business, and while awareness of our own mortality is an important part of that, awareness and activism around racism, violence and injustice in end-of-life care is essential.

Death ambassadors

Figures like Dosani are making social media outreach part of their teaching and care practices. In recognition of the importance of creating death supportive communities, I also started an Instagram account, @death.ambassadors, to chronicle my death teaching.

At the end of each death course, I offer students the opportunity to be a “death ambassador,” in recognition of their new level of death awareness that could help to foster healthy conversations about death and dying in our culture.

Some of my students have also created their own death-awareness social media accounts, and found themselves supported by a death-positive community of educators, end-of-life companions, funeral directors and death doulas.

It is a universal truth that one day we are all going to die and that means we all have a serious stake in death education.

When it’s your turn, or the turn of someone you love, don’t we all need people who have considered how to support us in navigating dying and death? Let’s do the work to make that a reality for everyone.

About the author: Susan Srigley is a Professor of Religions and Cultures, Death Doula & Death Educator at Nipissing University, Ontario

Comments