Canadian households: Among highest debt-to-income ratios in the world

by Armine Yalnizyan

In the past few weeks some of Canada’s most respected economic authorities, including Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney, have voiced concerns over the fragility of the recovery, globally and at home. Now Paul Krugman joins that chorus of Cassandras, pointing his finger straight at the wishful thinkers who say Canada’s heavy lifting is done when it comes to economic recovery.

Speaking at a conference of lawyers, he reminded his audience that government balance sheets are only part of the problem going forward.

Household budgets are a bigger part of the economy, and re-balancing them will take a lot longer if governments prioritize putting their own fiscal house in order first. On this front, Krugman notes, Canadians have little reason to be sanguine about what happens next.

Though our labour market did not lose jobs for 27 long months as in the U.S., he reminds us we have one of the worst debt to income ratios in the world.

In fact Canadians have the worst debt to income ratio of 20 OECD nations.

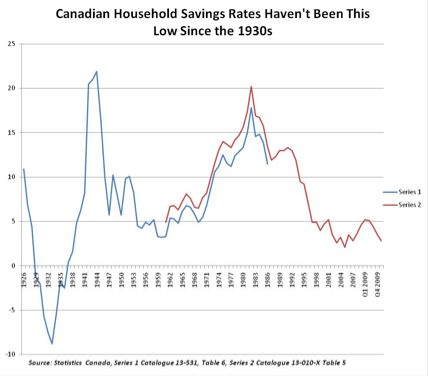

He went on to deliver this shocker: today Canada’s household savings rate ($2.80 on every $100 dollars of household income) is less than half that of the U.S. ($6.40 on every $100). He said that’s the first time this has occurred since the 1970s.

The message about how exposed Canadians are, and which balance sheets need to be balanced first, is one worth repeating. Indeed, we at the CCPA have been repeating it since last April, with the publication of Exposed: Revealing Truths About Canada’s Recession. By any historic standard, this is no routine recession.

Here’s a sobering factoid that takes Krugman’s shocking comparison even further: You actually have to go back to 1938 to see Canadian household savings rates this low.

In 1992 (where we are now in the cycle, two years after the economic crisis began) the national savings rate stood at 13%. At that time the Bank of Canada’s prime rate was 7.5%, the average 5-year mortgage commanded a 9.5% rate of interest, and a second decade of assault on middle class earnings was yet to begin in earnest.

That was then, this is now.

Interest rates are at historic lows, lower than even when the Bank of Canada was first put into place, in 1934. That means it is easier than ever to borrow and less attractive to save. But that ignores a bigger truth: it’s getting harder to save, and not just for the poorest among us.

Unremitting increases in the costs of housing, education and transportation while incomes are stagnant (or worse) means it may take a long time for savings rates to climb.

Rising debt levels since the crisis began is one obvious indication of how hard this is going to be: In the fall of 2008, before the crisis hit, Canadians owed $1.40 owed on every dollar of disposable income. That broke all previous records. At last count (1st quarter of 2010), the average Canadian household owed $1.47 on every dollar they took in.

Krugman reminds us of what we all know: interest rates have nowhere to go but up. Indeed, it’s a fine balancing act, leaving behind an era of easy money, and making ends meet.

This article originally appeared on the website of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and is reprinted with permission.

Comments